Article: The fascinating heritage of Zardozi Embroidery

Photographs & Article by Ranadeep Bhattacharyya and Judhajit Bagchi

Uluberia, a small town on the banks of the River Hooghly in the Howrah district of West Bengal, would have been just another town in India, but for its unique contribution to India’s craft heritage. It is here till date in the quaint darkness of their humble huts, the nimble fingers of the Mughal court-embroider descendants keep alive the rich tradition of Zardozi and Arri embroidery- the beautiful gold and silver metal embroidery, which once used to embellish the attire of royals.

Even though Zardozi is believed to have its origin in Persia (Zar in Persian means gold and Dozi is embroidery), the use of gold and silver thread work goes back to ancient India, its mention being made in Vedic literature, the Mahabharta and the Ramayana; the Ajanta figures being their visual manifestations. But it was only under the royal patronage of the Mughal king ‘Akbar the great’, that Zardozi and Arri embroidery reached its zenith and was extensively used to adorn the costumes of the court, wall hanging, palanquins, scabbards, regal sidewalls of tents and the rich trappings of elephants and horses. A closer look into the miniature paintings of the royal court from the Mughal era reveal the elaborate and highly refined floral motifs in gold embroidered on the princely attire.

After flourishing seamlessly in the initial Mughal period, the craft declined during the rule of Emperor Aurangzeb when the royal patronage extended to craftsmen was stopped. The onset of industrialization in the 18th and 19th centuries was yet another setback. Out of work, while many craftsmen turned to other occupations, others left Delhi to seek work elsewhere. With the emergence of the Muslim nobility in Bengal, the craftsmen found rich patronage and settled down in the banks of River Hooghly in the Uluberia and Ranihati area, naturalizing the Zardozi and Arri craft to Bengal. At present, over 75% of the population of Uluberia depend on this craft for their livelihood majority of them being Muslim craftsmen who carry forward the heritage of their forefathers. While men work collectively in workshops, women practice the craft inside their house in between their daily chores.

Sitting inside his damped workshop, Sheikh Mosibur Rehman; a fifth generation Zardoz (a Zardozi craftsman) nostalgically recalls how his forefathers were referred as ‘gardeners of garments’ in praise of the intricate floral motifs they perfectly and painstakingly embroidered with their small crochet-hooked needle! Traditionally, the art of Zardozi only used gold and silver wire along with precious gems and diamonds but with time silk and other shining threads like dabkaa (a combination of gold and silk threads), kasab (silver or gold-plated silver thread) and bullien (copper and brass coated threads) replaced them. Precious gems have given way to sitaaras or metal stars, round sequins, glass and plastic beads, even though the process of embroidery remains the same.

Unlike, the opulent royal karkhanas (court workshops) of the Mughals, today in the cramped workshops, the entire economics of the trade has changed even though the effort remains the same. Azizul Shah, another Zardoz practicing the crafty for over three decades says it takes almost 25 years for any craftsmen to gain expertise in Zardozi art. Hence, children start learning this art at a very early age observing their family members at work.

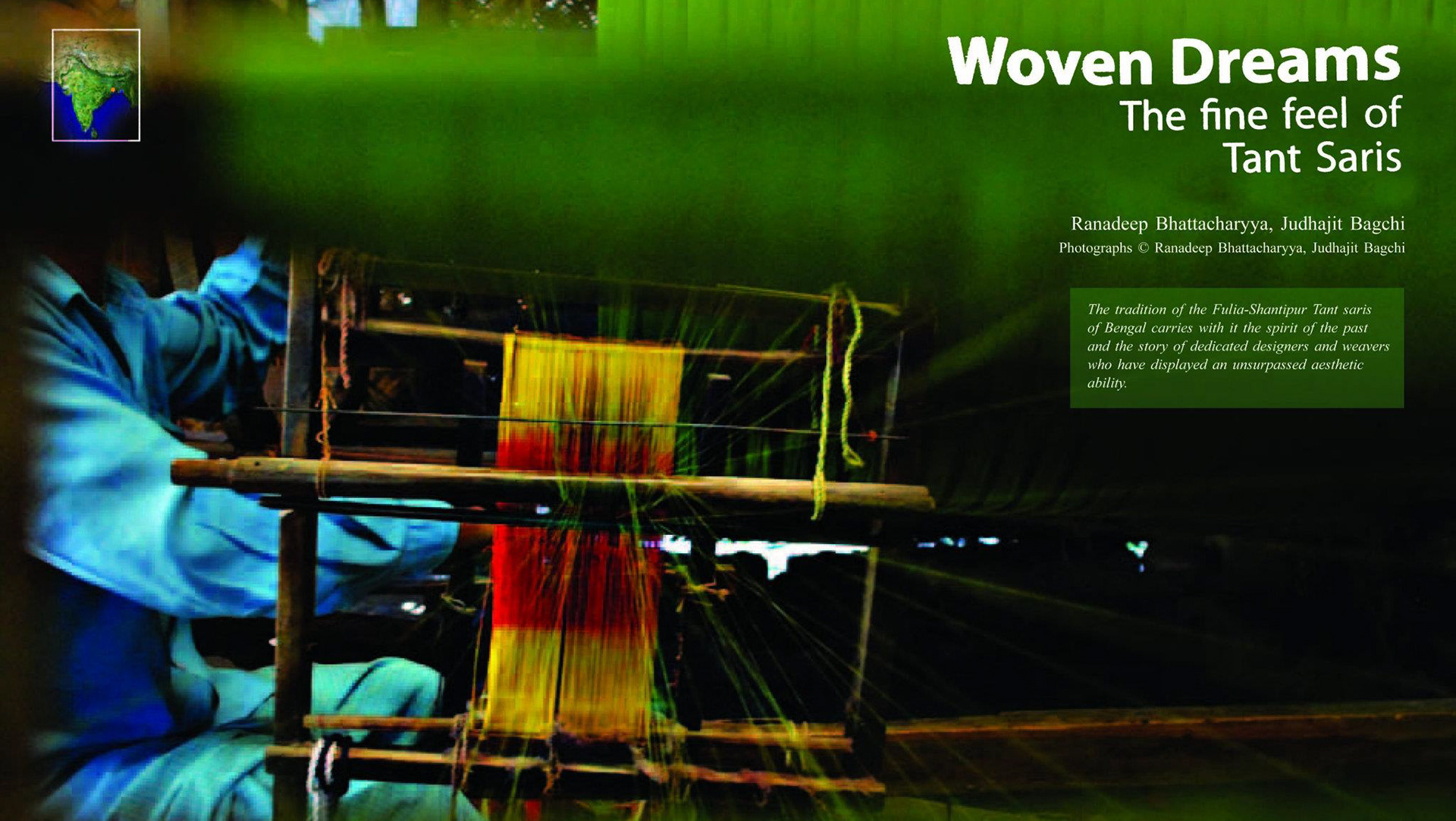

The process in which Arri and Zardozi embroidery is done is quite intriguing. At first, the fabric (generally silk, velvet, brocade, crepe and georgette) is stretched taut over a frame called the adda and stitched on to the wooden frame using thick cotton thread giving it uniform tension. Next follows the step of drawing the embroidery design on the fabric.

Zardoz Sheikh Mosibur Rehman informs that unlike its Persian counterpart where only floral motifs with sacred Quranic verses were the subject of design, Indian design patterns are more imaginative. Flowers, leaves, creepers have been widely used as design motifs right from the Mughal era with birds like peacock, parrot and pigeons being integrated into the design much later. As the craft travelled to the royal courts of Rajasthan, Marwar, Bengal and Gujrat, innovations happened and the design patterns became more geometric merged with the floral themes.

The process of printing the design on the fabric is also unique. After the design is drawn on a tracing paper, holes are pierced all along the lines using a needle. To transfer the design on to the fabric, a mixture of kerosene and chalk is made and rubbed with linen on the tracing paper. The liquid seeps through the holes and the design impression stays on the fabric.

The real work of embroidery starts from now. The craftsmen sit cross-legged beside the adda with their box of coloured threads, sequins and their only tool- a needle with a hooked end. Both Arri and zardozi follow the appliqué method of embroidery wherein the needle is pushed through the fabric from the top while the craftsman holds a retaining thread below the fabric which gets pulled up the hooked end of the needle the next time. In this looped manner, the small yet fine stitches create a dense mesh of exquisite work of art.

While Arri looks like fine chain stitch, Zardozi on the other hand has finer designs as while the craftsman’s hand above the cloth works the needle, the hand below the cloth ties each stitch - making Zardozi products not only beautiful but durable.

Even in this age, the embroidery is completely done manually by the craftsmen without the use of any machinery whatsoever. The work is so intricate and strenuous to the eye that it takes almost 2-3 days to complete a six meter sari with 5-6 craftsmen continuously working on it. During the peak business season that coincides with Dushera, Diwali and Eid, the workshops are cramped with over 12-14 craftsmen working on a sari for over 18 hours at a stretch. While an apprentice gets paid about Rs 2 per hour, the expert craftsmen earn about Rs 18 per hour.

Once the embroidery is complete, the thread is flattened out with a light-weight wooden hammer and the fabric is ready to be dispatched to the reseller. While a handful of craftsmen have small outlets in Uluberia itself, the bulk of the work happens mainly on contract basis from cloth merchants all over the world who buy the embroidered fabric and transform it into finished products like saris, kurtas, lehenga-choli, salwar-kameez or other home décor paraphernalia that keep reminding us of our rich cultural past.