Article:

Woven Dreams...TheTant Sari tradition of the Fulia- Shantipur Tant Saris of Bengal

Text & Photographs:

Ranadeep Bhattacharyya & Judhajit Bagchi

Bengal has an age-old tradition of producing super fine cloth. The art of weaving in the pre-partition undivided Bengal retained its perfection from the elaborately designed adivasa of Aryan days to the finer motifs of the Mohammedan Period. The story of Aurangazeb rebuking his daughter for being naked when in reality she was wearing seven layers of super-fine Bengal handcrafted muslin goes on to explain the finesse of the weaver’s creations. While muslin adored the princely courts and the courtesans, the common folk draped themselves in the special handcrafted Bengal cotton saris known as ‘Tant”.

Tant saris owe their popularity to the hot and humid weather of coastal Bengal where it they provide comfort to the wearer by virtue of its their lightweight nature, making it handy for every occasion.

“Contrary to the popular image of a Bengali lady in a white tant sari with thick red border, these high quality cotton saris come in a host of vibrant colours with gorgeous borders and a papery soft texture. The latest improvisation is the tant benarasi made out of cotton with rich motifs equally pretty as its original counterpart - the benarasi silk sari,” says Dilip Basak, a fourth generation tant weaver, as he folds a freshly woven sari from the loom in his current workshop at Fulia in West Bengal.

A discussion on the handloom sari of Bengal cannot be complete without the mention of the geographic twins, Shantipur and Fulia, located in the Nadia District of West Bengal, the birthplace of the great Bhakti movement Saint Shri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, whose songs still resonate in Bengal.

There are records of handloom sari weaving activity in Shantipur as early as the 15th century. Weaving flourished throughout the medieval era and, during the early part of the 20th century, the famed indigo-dyed midnight-blue Neelambari sari made the Shantipur sari a household name for their fine texture and uniformity. In the decades leading up to independence, Shantipur saw a gradual inflow of modern techniques in terms of improvement in the handloom and the introduction of the Jacquard loom in the 1930s, which is still used by the weavers.

During the partition of India, the demographics of Shantipur region went through a sea change as Hindu weavers fleeting the erstwhile East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) settled down in large numbers in Fulia, neighbouring Shantipur.

The village industries rehabilitation initiatives of the then West Bengal government aided in providing each weaver’s family with a single loom and two rooms to practice their craft and five acres of land to build their house on.

Weaver Shyamapada Basak, who had migrated from East Bengal in 1948 fondly recollects, “Since the time the colony was formed and security to life was reassured, there were thousands of weaver families (mainly Basaks) like us who migrated from their hometown in Tangail District near Dhaka in modern Bangladesh, famous for the incomparable Dhakai Jamdani sari, to our new home in Fulia.”

Dhakai Jamdanis were traditionally hand-embroidered in the loom from original European cotton. To produce rich effects, bleached cotton, black-dyed cotton, gold and muga threads are used. The ground threads were always fine grey cotton. The weavers of Bengal, with unlimited patience and amazing hereditary skills, produce these fascinating figured jamdanis- the most artistic and expensive creations of the Dacca loom immediately identified by its very fine texture resembling muslin and the elaborate and ornate workmanship. The demand and popularity for this priced artifact was such that during the Mughal rule in Bengal, the manufacture of the jamdanis was a government monopoly.

Over the years, through cultural and artistic intercourse, the Fulia weavers integrated their craft with the Shantipur style and developed their own version of the original Dhakai Jamdani, called the ‘Fulia Tangail’.

Basak adds that the “Fulia Tangail incorporates vibrant colours and large, intricate designs woven in double jacquard loom to produce floral or geometric motifs. However, it has a softer feel and sparser distribution of motifs than the original hand woven Jamdani saris.

Today, the cotton saris from Shantipur and Fulia together are world-renowned as the famous Bengal Tant saris.

Walking in the narrow lanes of Fulia, one is greeted by the incessant murmur of the looms endlessly at work, weaving away yarns full of centuries of traditions. Weaving on a handloom is done by intersecting the longitudinal threads, the warp (that which is thrown across), with the transverse threads, the weft (that which is woven). A peep from the window greets one’s eyes with the large mesh of threads mounted on the looms with the weaver seated in an upright position with his feet constantly pushing against the treadles and his hand constantly pulling the cylindrical wooden lathe, weaving a single thread cloth with every pull. “But weaving the threads into a sari is the last stage of the entire process of making a tant sari. The main process starts as soon as the raw material arrives from the mills,” informs the seasoned weaver Basak.

The raw material for the tant saris, super fine 100X100 to 120X120 counts cotton, is currently exported from the mills of Surat in bulk quantities. The bundles of cotton come in its raw kora (cream) colour and the first step is to rigorously wash them by beating them with water to make it free of any factory chemicals.

Once washing is done, the bundles are dried in the sun and sent off to dye in the colour specified by the cloth mahajans or merchants who mainly provide orders to the weavers to manufacture these saris.

“Dyeing” says Swapan Basak, the owner of the dyeing workshop at Fulia, “is a specialty job requiring about 10- 15 people to complete the entire process.”

The dried cotton bundles are first bleached to make it white, again dried throughout the day and then dipped in boiling hot water with specific colour proportions as per the shade required. Both natural as well as artificial colours are used at the dyeing mills. Red and yellow being the most common combinations for tant saris are cheaper as compared to the uncommon parrot green, indigo blue and bottle green colours that cost almost double. Generally as the colour becomes darker, the cost increases as it requires use of more colour in proportion to the water. After the cotton is dyed, the labourers lay them on the bamboo poles in the middle of the open fields in order to sun-dry them.

Once the cotton is dyed, the bundles are sent to the weavers who start the first process of assembling the thread into bobbins. The women of the weaver’s family are also involved in the profession as they rigorously starch the thread with puffed rice to give it strength and additional tenacity. The thread is then soaked in water for hours to bring permanency to the colour and later dried and spun on the spindle assembled into small bobbins.

The small bobbins are then mounted on a frame whereby each thread passes through the narrow metallic cylindrical cones called shana, making it super fine as well as sturdy. The cotton threads are then wound in layers on big bamboo drums holding enough thread to make 30-35 saris. The assorted threads from the drum are then wrapped on a rounded wooden log, which in turn feed the loom to facilitate weaving of the tant sari.

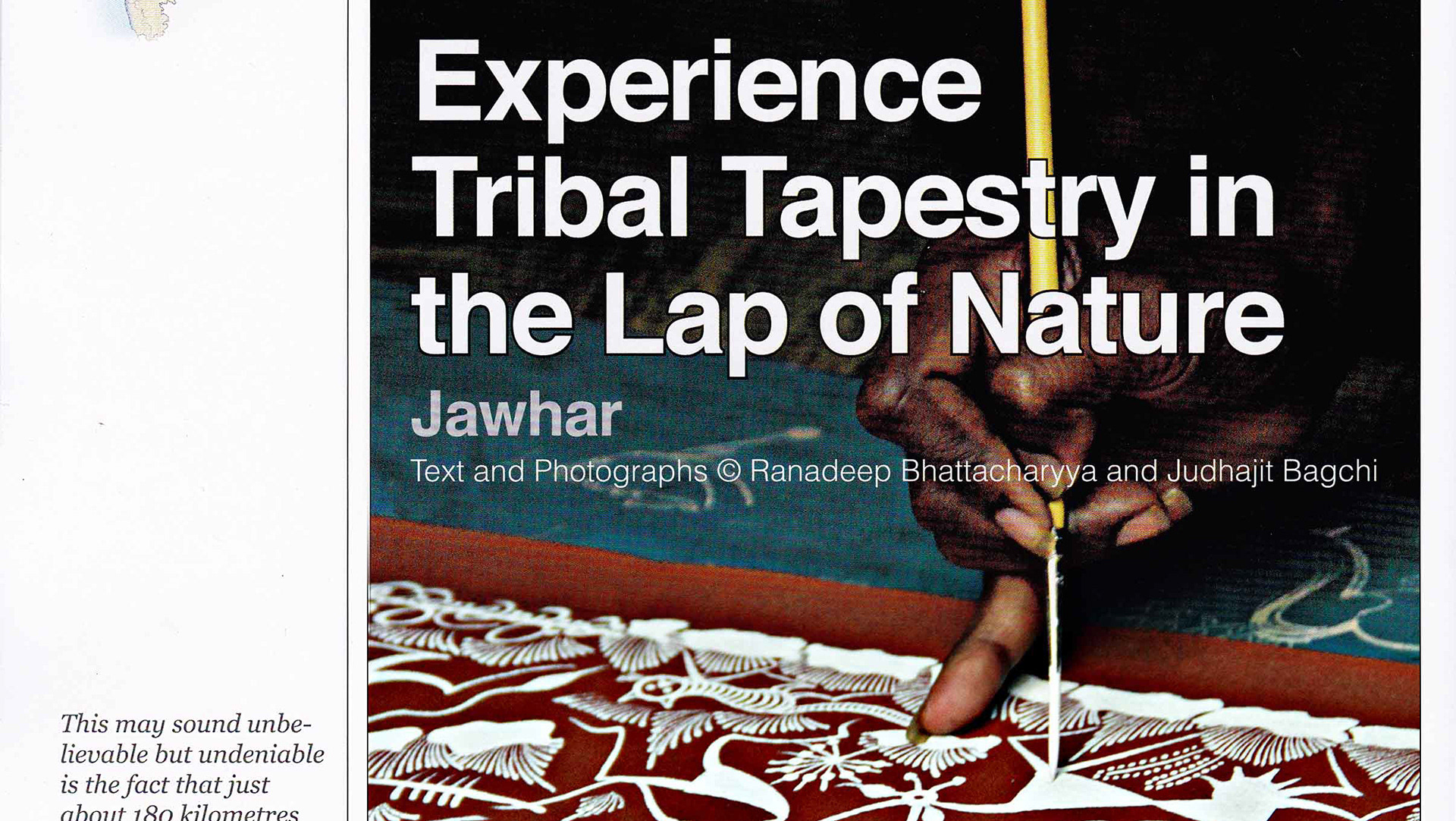

Another major task before weaving is mounting the designs on the loom to be made on the sari. In medieval Bengali literature, there is mention of a large number of traditional designs that were extremely popular in those times. The prominent one being chandmal sari, derived from the round motif that depicts the moon; bhomrapar sari, derived from the hornet and the motifs of the bumble bee mainly in indigo, black, red and chocolate traditional colours and the brindamani sari, derived from its border that depicts two peacocks, face-to-face on a tree. The drawing of the peacock is in the traditional style and is done with much sensitivity. While some of these designs have stood the test of time, new less ornate designs have become more popular now.

Once the artist draws the design of the border and the body of the sari, the same is divided into graphical quadrants and mathematically perforations are made on soft cardboard cards in tune with the design. The perforated design boards, ranging from 200-2000 in number depending on the intricacy of the designs, are then suspended from the loom with the help of iron weights or even bricks in many cases. With time though designs are made on computers, the process of conversion of the same into cardboard perforation cards has remained a tedious affair involving lots of time and dedication coupled with years of experience.

Finally, the sari is ready to be weaved and on an average it takes almost ten to twelve hours to weave a tant sari with the simplest of designs. Since weaving on the handloom demands lot of physical strength, women refrain from the actual weaving of the sari and mainly men work diligently to produce magnificent weaves. On an average, they work for almost 14-16 hours a day, sitting in the dimly-lit small tin shed workshop that houses 4-5 looms. Occasionally, the weaver polishes the loom with wax to facilitate smooth flow of the threads.

Another unique feature of Fulia-Shantipur saris is their finishing. Weaver Balaram Basak, while rolling a ball of popped rice paste on the sari points out, “Once the sari is woven, before taking it off from the frame, the weaver for one last time has to apply size paste (made from sago or popped rice) meticulously with his hand to give additional luster and shine to the freshly woven tant.”

On an average for every sari, the weavers get around Rs 150 – Rs 300, depending on the intricacies of the design. The months preceding to Durga Puja is the most busy work season for the weavers as demand for the saris are very high at this period. Though the scenario has remained the same till date, but in the past few years with the increase in the cost of raw cotton by almost 80%, weavers find it difficult to sustain in the business. As a result, many weaver families have shifted to other occupations thereby increasing the workload on the remaining weavers all year round who now find it difficult to cope up with the huge demand. The only solution as per the weavers is the urgent need of government intervention and price capping and subsidizing of raw cotton.

Displaying the finished product on the cane mattress in his small living room that doubles up as a store room for the saris, Tarak Basak, a the third generation weaver says, “The traditional Dhakai Jamdani sari borders had mainly lotus pattern, lamp pattern and the famous ‘aansh’ pattern. But with time, from the use of a single colour on the border, the weavers began to use two to three colours to give it ‘meekari’ effect.” Thus was born the dainty and exquisitely fashioned special Fulia Jamdanis, which are literally ‘woven dreams’ and the most sought after saris today.

With time, tant saris have stopped being the everyday wear for women who prefer either salwar kameez or western wear over handloom because of the maintenance that these fine fabrics demand. In keeping with this trend, the Fulia- Shantipur weavers are now venturing into producing scarves, stoles and other fashionable items in tant with muted colours to suit today’s sensibilities.

Despite its antiquity, the Bengal tant handloom industry is by no means primitive or silted by tradition. The weaver is an artist capturing the colours in the environment around him and transferring them to the fabric he weaves. The weaver carries in his eyes and hands an incredible creative force, which is expressed through unsurpassed technical skill and knowledge of design and colour. Till date, traditional fabrics can provide considerable strength and inspiration to the producers and the designers of the emerging generation.

End.